Sufjan Stevens is one of my musical heroes. I don't know when I decided this, but you can tell it's happened when you start making assumptions about an artist based on small inferences. You concoct a fascinating back story and song meanings that only you, the avid fan, understand. It's the reason you never meet your heroes, yet the basis of all hardcore fandom.

This tendency to fill in the blanks of your favorite artists is a little bit creepy, a little bit wrong, but completely within your rights as a fan with nothing better to do. It is part of the price of being a public artist; everyone gets to interpret and participate in art's communal conversation.

Sufjan Stevens is the kind of figure that gives you a lot of blanks. His interviews are rare, his songs are wrapped in mystery or mixed with fiction, and he is overall hard to figure out. We know that he is a writer, from Michigan, a multi-instrumentalist and a Christian. He also released one of the greatest albums in modern independent music, ILLINOIS, which was a sprawling work about the state, past and present, fact and fiction. It won a million awards including album of the decade.

But ILLINOIS was 5 years ago. Since then, he has put out a compilation of b-sides, a mixed-media orchestral suite, and commissioned a remix of one of his earliest electronic albums. In terms of original material, every once in a while we would get a song or two, small morsels at best, usually on charity-based compilations like Dark Was The Night.

ILLINOIS made Sufjan a Big Deal, and then he disappeared. No follow-up album, no late night TV appearances, not even a new t-shirt. The Arcade Fire hit on fame around the same time, and they've put out two albums, soundtracked some films, and played shows in support of Barack Obama. The Arcade Fire maximized their newfound notoriety, stopping short of oversaturation. Sufjan, meanwhile, hid away.

The people wanted an album for every state, but in the grand tradition of Bob Dylan, he did not want to play ball with the expectations and myth created around him. Dylan was portrayed as an activist and prophet, but never went to rallies with Joan Baez and grew tired of "finger pointing songs." Sufjan grew tired of his banjo aesthetic and ditched the civic pride gimmick almost immediately.

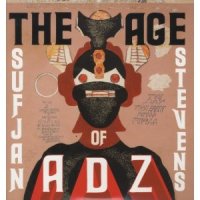

It is 2010, and with short notice and no hype, we are told a new album is dropping in weeks. The AGE OF ADZ is the first proper studio album by Sufjan since 2005. The temptation is to say that it is radically different. But if you dig deep enough, you'll find its roots in some of Sufjan's earliest work, and it's still the same guy you imagined. The AGE OF ADZ, then, is a growth.

It first strikes you as a big departure because Sufjan bought a synth pad and a drum machine. I'm careful not to call it electronica - it is clear he is simply using electronic sounds and synths and effects, but in a distinctly Sufjan way. He is not taking advantage of the cyclical nature of beats, or the warm extended buzzing of bass synths, or even playing up any sort of danceability. If you imagine the strange, alien bleeps & chirps that seem to play almost at random in "I Walked" replaced with, say, violins or trumpets, you would get a decidedly Illinois-era song.

There are other major keystone differences. For the last three proper album releases, Sufjan gave himself a prompt: Write about a state. He imbued dry historical trivia with a humanizing emotional core. Now, without any of that framework, he is writing purely from an expressive place, taking you into his living room to tell you something that has been bothering him. It is thrilling to get a glimpse of the personal, like peeking through a door slightly ajar. For example, traditional love songs by Sufjan Stevens were a rarity, with the softly drifting "Holland" the standout among them. AGE OF ADZ has them in force, and it's like a demigod gaining mortality. Instead of projecting a love song onto a fiction about a girl with bone cancer, he is simply telling you: I was in love, and things got messy.

As a creative writing major, Sufjan knows that something like "Casimir Pulaski Day," was a form of showing, and his recent Adz work is explicitly telling. Normally this is considered a sloppy move (at least in beginning writing courses), but you feel the intent of plain, whittled down language here. No longer is the songwriting flowery and purple and thick with metaphor. It is strange, to hear someone as talented and eloquent as Stevens write and sing so frankly: "I think of you as my brother / although that sounds dumb" on "Futile Devices" or, now infamously, "I'm not fucking around" on "I Want To Be Well."

"It was about allowing myself to express those feelings in very matter-of-fact, almost cliched terms," says Sufjan. There is a value in incisive, no-frills writing.

In that same sense, there is value in ugly versus pretty. It's exciting to hear Sufjan really bite down into chaotic dissonance. Whereas ILLINOIS gave you infinite pretty, AGE OF ADZ isn't afraid to use anti-melody to evoke some darker, grating feelings. Just listen to that scratchy sandpaper guitar solo on the epic album ender, "Impossible Soul" -- it would sound accidental were it not so appropriate to the song. These aren't random bleeps and bloops interjected at strange intervals, this is calculated dissonance, the anti-pop for a song bigger than genres.

Then there is his voice, or more specifically, his singing. Tuning out the noise, focusing solely on the vocal melody, you start to hear an R&B sensibility. He is not an R&B singer, but he is doing the best he can to take after their soaring, riffing, tremolo style and it only comes off as endearing. He's taking his regular, human voice to the peaks and valleys of pitch. His old work like "Decatur" and "Casimir Pulaski Day" were characterized by his breathy, barely-a-whisper voice. He's still not belting it out (he probably doesn't have the lungs to pull it off) but he's clearly using his soul more. It's emotion over intimacy, emptying the heart over bringing you in close.

So how are the songs? There isn't nearly as much sonic variety as ILLINOIS or even THE AVALANCHE, as the synths can blur together more than acoustic instruments. But what it loses in individual distinction it gains conceptual wholeness. Album opener "Futile Devices" is a short, easy album opener, reminiscent of the Sufjan you concocted in your brain. But then he switches that bait with "Too Much," which is composed of weird off-beat claps and hits that barely stick to a pattern.

The title track, "The AGE OF ADZ" strays from much of the electronic noises and just brings you the full fury of orchestra, yet it departs from Sufjan's established reportoire by sounding like a harrowing. Yet it's not emotional catastrophe harrowing, it's Hollywood monster movie harrowing. Indeed, the intro sounds like something out of King Kong or the scariest parts of The Wizard of Oz. It is also the first appearance of some truly beautiful and simple lyrics: "When I die / I'll rot / But when I live / I'll give it all I've got." I also wonder if he's referring to the Sufjan following masses, imagining our voice blatantly saying to him: "We see you trying / to be something else that / you're not / we think you're not" or "The gorgeous mess of / your face impressed us / Imposed in all its art."

There's a point about 5 minutes in where it steps away from the epic bass drum in favor of majestic drum corps. The doomsaying choir suddenly becomes a chorus of angels, Christmas bells line the way, and the strange electronic rhythm section take a backseat to the wide chamber echo. It is stripped down further 7 minutes in to center on simple finger picking and some open heart confession:

For my intentions were good intentions

I could have loved you, I could have changed you

I'm sorry if I seem self-effacing, consumed by selfish thoughts

It's only that I still love you deeply

It's all the love I've got

"I Want To Be Well" is the song that every fan talks about, at least at first. The introductory verse puts us squarely back in the Illinois mold, with a lyrical focus on "ordinary people" and "extraordinary histories" as well as his signature fluttering butterfly flutes. If you changed the electronic instrumentation to a banjo and a trumpet, it would have fit in right before "Chicago."

But barely two minutes in, Sufjan takes the from Little Miss Sunshine down a backroad into Dreadtown. Set to a sudden solo picking, he recites over and over like an incantation, a wishful plea, the words, "I want to be well, I want to be well, I want to be well, I want to be well." Somewhere, someone is weeping to that. It becomes a prayer, a mantra, the purest yearning for the most universal of wishes: I want to be well. It encompasses everything.

With this scope, Sufjan has written one of his most dramatic pieces ever. It is relentlessly loud, with thumping, dramatic, pounding hits at the end of every measure. Sufjan Stevens sounds like he can do nothing else but shout with a soulful conviction: "I'm not fucking around / I'm not / I'm not." The novelty of Sufjan cursing is what gets people, and it's smart deployment. The debut of this new image of Sufjan adds conviction and seriousness, the way curse words are supposed to.

Then there's "Impossible Soul." I could write thousands of words on this song; extrapolating, deconstructing, projecting, straight making shit up. Normally, a song of about 7 minutes is a feat. Sometimes bands get ambitious and play around the 10 minute mark. Sufjan decided to be ridiculous and epic, and release an 11 minute song and a 17 minute song to bookend his All Delighted People EP. So what can he do with ending his eagerly awaited first album in 5 years? He can only top himself and chart a path to a 25 minute titan.

"Impossible Soul," which I also think is one of the best combinations of two words in the English language, was one of my favorite songs when I heard the live recordings from his pre-release tour. It was 9 minutes then. For the album, Sufjan has grafted on three more movements, which are more like wholly separate songs, except for the running theme of love and possibility. The first movement is beautiful: It's a unique approach where sparse robot keyboards take a backseat to dancing vocal melodies. A bass line fills in the void areas between key presses with a sort of counter-melody, hitting all the complimentary opposite notes in the scale. The drums have a bit of ADD, hyperactively doing their own thing way in the corner. It's as if the bass & drum have changed roles with the keyboard & guitar. The keyboard & guitar are more like timekeepers, while the bass & drum try and build a melody.

You hear Sufjan's earnesty when he ramps up the emotional intensity on certain lines: "And all I couldn't sing / I would say it all to you if I could get you at all," followed by, "Don't be a wreck / trying to be something that I wasn't at all." It sounds at first that he is speaking to an equally jilted lover, although it could be a plead with his fanbase and the devils of expectations, for all I know. Then there's this:

You said something like: all you want is all the world for yourself

And all I want is the perfect love

Though I know it's small

I won't love for us all.

Shara Worden brings her haunting voice to the second movement, like an angel descending to give us wisdom from above: "Don't be distracted," she says. "For life in the cage / where courage's mate / runs deep in the wake / For the scariest things / are not half as enslaved."

It's at this point the song's core, long build starts. The rhythm shifts into second gear, builds anticipation with an eye to the far horizon, until the crescendo ends in a vaporizing. The words end with a breath, and all that is left is a dead, ambient dreamscape of noise and ghosts of lines once sung. A single piano note in the background surfaces to give us shape, and the song begins again from the primordial soup. Then the verse comes and it's straight up T-Pain/Kanye West styled auto-tune.

This was another point of friction for Sufjan fans. Auto-tune is an instrument, just like any other, and it can be used well or poorly. It's not as if he's using it to cover up his vocal inadequacy, he has just spent an hour showing it. It's an effect, just like the way Elliott Smith would multitrack his voice to give it artificial texture on most of his songs. It simply sounds cool. That ought to be enough.

"Stupid man in the window," he sings with an intangible indignation, "I couldn't be at rest." Obsessives may pinpoint this as a callback to Carl Sandburg in "Come On! Feel the Illinoise!" which featured the poet approaching Sufjan's window and asking him to "improvise on the attitude, the regret, of a thousand centuries of death." Is it resentment of all that Illinois has wrought? Personal details we couldn't hope to decode? The mystery is intact.

This movement is likely the least Sufjan-esque out of anything, taking the most steps towards "traditional" electronica and dance music, but it doesn't last long. We are segued into this weird Kidz Bop-like call-and-response dance ditty. "It's a long life! / only one last chance! / Couldn't get much better! / Do you want to dance?" It is absolutely sugary sweet, optimistic, and the strangest 180 degree turn that you can't help but love it. It is almost dumb, and you think, that has to be the point. "Boy, we can do much more together / It's not so impossible!" sings the crowd, which must be populated entirely by cartoon rabbits.

There is an unrelenting sunshine to it, characterized by the fast lines that lift you up and over the murky depths you were previously submerged in. It is ridiculous, in the best way possible, even when he breaks out the TALKBOX to tell us it's not so impossible. But innocence fades, and a distinctly masculine and looming group takes over the hook: "Boy, we can do much more together." Except now, it sounds foreboding, like a zombie horde closing in.

The last movement kicks in during a gentle hum of darkness - intricate finger plucking breaks through, and the voice of Stevens, once again, plainly, simply, and all up in your heart. How do you end a wild ride of frustration to anger to unfiltered joy? With the complicated greys of real life, real relationships:

I never meant to cause you pain.

My burden is the weight of a feather.

I never meant to lead you on.

I only meant to please me, however.

It's the sort of honest self-deprecation that characterizes Tim Kasher more than Sufjan Stevens. It feels shockingly earnest, and lily-livered no more, bordering on cruel: "Did you think I'd stay the night? / Did you think I'd love you forever?" Whereas once we were plastered with cries of the wonders of life and love, of "It's not so impossible," the song finishes on the comment from his lover: "Boy, we made such a mess together."

And that's it. There is no way to end that song other than a fade out. 25 minutes, and you are taken on a whole range of emotional extremes, complicated moral colors from black, white, grey and purple. The scope makes you feel like every sound on earth had been utilized, as well as some new ones. It is exhausting to listen to, like running a marathon, and when it is over you cannot believe what you have just done. Few songs can reach this size while still making every second feel necessary. It feels like being dragged through the mud of a tumultuous relationship. There is the dissatisfaction, the doubt, the falling in love, and the strange, undefined aftermath where nothing is certain but you accept it all in your tin-can heart.

There are other winners on the album; "Vesuvius" is a strange, dark chant. "Now That I'm Older" is a ghoulish introspection. Mostly, the Sufjan listener can come away with a feeling that the game has changed. It is the wonder of complexity and simplicity, catchiness and dissonance, everything working together in concert. It's about love and friends and art. It is a musician spending months playing with drum machines and reworking sounds in a studio, to twist the pressure valve in his head in a new direction.

Technically, that's the only way to interpret someone's art. But there is fun in pretending that you get it, that you see through the code for the holy truth. You can only take in all the sounds and words, jumble them in your head and let it marinate until you have an idea you love. AGE OF ADZ is a journey, but not the kind that takes you from a small town over mountains and across oceans. It's bigger than that. This time it's a journey through a lifetime, from a youthful exuberance to the uncertain future.